To what extent does Bloom’s taxonomy actually apply to foreign language teaching and learning?

Bloom’s taxonomy of higher order thinking skills has acquired a mythological status, amongst educators. It is one of those reference frameworks that teachers adhere to with some sort of blind allegiance and which, in 25 years of teaching, I have never heard anyone question or criticize. Yet, it is far from perfect and, as I intend to argue in this article, there are serious issues undermining its validity, both with its theoretical premises and its practical implementation in MFL curriculum planning and lesson evaluation in school settings.

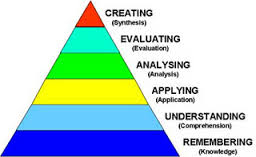

Why should we be ‘wary’ of the Bloom taxonomy, as the ‘alarmist’ title of this article implies? Mainly because people forget or fail to consider that the Bloom Taxonomy was not meant as an evaluative tool and does not purport to measure ‘effective teaching’. In fact, the book in which the higher order thinking skills taxonomy was published is entitled: Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: The Classification of Educational Goals. However, in the last twenty-thirty years, the taxonomy has often been used in UK secondary school to evaluate teaching performance and how effectively students are engaged in higher order thinking skills. The main problem lies exactly here, the hierarchy that Bloom and the authors of the revised version (Anderson et al, 2000) devised being not necessarily a valid construct, especially not from a Foreign Language acquisition perspective rooted in sound Cognitive theory.

The first set of issues refers to the top three levels, and to their hierarchical and sequential arrangement. On what basis does one decide, as the revised taxonomy does, that Creating (which in the new version replaces Bloom’ original construct: Synthesis) is a higher order cognitive skill than Evaluating? Let us look at the following definitions of the three higher skills (adapted from: http://thesecondprinciple.com/teaching-essentials/beyond-bloom-cognitive-taxonomy-revised/ )

- Creating: Putting elements together to form a coherent or functional whole; reorganizing elements into a new pattern or structure through generating, planning, or producing. Creating requires users to put parts together in a new way or synthesize parts into something new and different a new form or product.

- Evaluating: Making judgments based on criteria and standards through checking and critiquing. Critiques, recommendations, and reports are some of the products that can be created to demonstrate the processes of evaluation.

- Analyzing: Breaking material or concepts into parts, determining how the parts relate or interrelate to one another or to an overall structure or purpose. Mental actions included in this function are differentiating, organizing, and attributing, as well as being able to distinguish between the components or parts.

In modern language learning all three levels equally require ‘depth of processing’ and the processes that underlie these three cognitive skills often unfold concurrently and synergistically in our brain. Think about the process of writing an argumentative essay in a foreign language: is generating ideas about a given question/topic a higher skill than evaluating their degree of relevance to that question/topic, as well as their suitability to the task and audience? Aren’t the two levels so closely interwoven for anyone to be able to separate them? And how can one determine which one is more cognitively demanding than the other, especially in a foreign language, where evaluating the accuracy of the grammatical, lexical and sociolinguistic levels of the output is extremely challenging? It is my belief that the two sets of processes and even the third one, Analyzing, are parallel in foreign language processing rather than sequential.

Let us consider, for example, the task of inferring meaning from a text containing a fair number of nouns, verbs, adjectives and discourse markers unfamiliar to the learner. The task demands the learner reader to analyze how each word relates to another syntactically and semantically (in terms of meaning); every time an inference is made about the meaning of each unfamiliar word, he/she will becreating meaning; every inference’s correctness needs to be evaluated. There you go! You have the three higher order thinking levels co-occurring in the execution of the same ’humble’ task – a reading comprehension. Yet, one wonders whether the average curriculum planner or non-linguist observer would perceive that task as ‘hitting’ the highest level of the Bloom taxonomy.

This brings us to the biggest issue with the way the Bloom taxonomy is used in education: the misinterpretation or failure to understand the true nature of language learning and the cognitive mechanisms that regulate it at various developmental levels. Being creative in Modern Foreign Language has to do less with content, tasks and production of artifacts, at lower levels of proficiency, than with creatinghypotheses about how the target language works, risk-taking (creatively seeking opportunities to test those hypotheses), coming up with communication strategies(creatively compensating for lack of knowledge of foreign language words), figuring out by oneself better ways to learn (creatively applying metacognitive strategies). The mistake often made by some language teachers is that they equate creativity in language learning to getting students to create a digital artifact or a language learning game; these activities tap into creativity but not the type of creativity that is conducive to greater linguistic proficiency. I will come back to this point later on.

Another important problem relates to the way humans process language in foreign language comprehension or production. The way learning occurs along the acquisition continuum is such that the brain gradually automatises the cognitive skills subsumed in the three categories the Bloom taxonomy places at the bottom of the pyramid. This process of automatisation speeds up the brain’s performance during language production so that cognitive processing can concentrate only on the higher levels of processing (analyzing, evaluating and creating) while executing the lower order levels ‘subconsciously’. Thus, for instance, in speaking, an advanced learner, having automatized the lower order thinking skills, will have to focus all his/her cognitive effort only on the top half of Bloom’s pyramid; on the other hand, beginner-to-intermediate learners will have to juggle demands from all six levels with potentially ‘disastrous’ consequences for grammar, pronunciation and accuracy in general. The obvious corollary is that engaging less proficient learners at the top three levels of the taxonomy in language learning can indeed happen, but through less cognitively demanding tasks in terms of processing ability.

Furthermore, a very important issue relates to the pressure many teachers feel to be working at the higher levels of the Bloom taxonomy as much and as often as possible, especially when they are being evaluated by course administrators. This is understandable but wrong and unethical on their part, when it comes to foreign language learning, as the nature of L2 acquisition is cumulative; jumping from one level to the next must be justified by the learners’ readiness to cope with the cognitive and linguistic demands that that level places on their procedural ability. Once one level is acquired, one can move to the next, each level providing a scaffolding (in Vigostkyan terms) for the one/ones immediately above. If a teacher feels that the learners are still ‘stuck’ at a level which needs more extensive practice, class work should stay at that level and it would be ethically wrong to move any higher merely to hit the top of the Bloom taxonomy.

Finally, and more worryingly, some educators posit that Puentedura’s SAMR mirrors the Blooms’ taxonomy, and fancy diagrams circulate on Twitter and teachers’ networks making the link explicit, further damaging teachers’ perception of what is expected of them in the 21st century Modern Foreign Language classroom. But does such overlap between the two models, actually exist? Does Bloom’s notion of Creative thinking overlap with Puentedura’s Redefinition? The answer is that the creation of a complex high tech product through ‘App-smashing’ or other digital media can only engage Creative Thinking with and through the target language inhighly proficient learners, but categorically not at lower levels of linguistic fluency and cognitive ability (see my article “Of SAMR and SAMRitans” on this blog for a more extensive treatment of this point). Only at advanced levels of linguistic proficiency can Redefinition be seen as overlapping with the highest order thinking skills in Bloom’s taxonomy.

In conclusion, Benjamin Bloom’s model, especially in Anderson et al’s (2000) adaptation, should be used for what it was meant to be: as a holistic classification of the different objectives that educators should set for students across the cognitive, affective and motor domains of learning. Bloom’s wheel (see picture below) was meant to help curriculum designers and teachers keep in sight the scope and main goals of effective learning. But Bloom was not an L2-acquisition expert and created this model before Cognitive psychologists of the likes of Eysenck, MacLaughlin, Baddeley and others unveiled the mechanisms involved in foreign language acquisition and processing and how Working Memory operates.

Foreign language teachers must be wary of any approach that straightjackets their efforts to enhance their students’ ‘healthy’ linguistic development by prescribing vertical progression at all costs. There are developmental stages in language learning which must be consolidated ‘horizontally’, so to speak, before we climb any cognitive ladder in the name of intuitively appealing pedagogic constructs. Horizontal progression is about developing Working-Memory processing efficiency (i.e. procedural knowledge), that is, the learner’s cognitive ability to cope with the huge demands that L2 comprehension and production put on his/her brain and motor-sensorial functions as he/she decodes, generates, retrieves or transforms knowledge into discourse under real operating conditions.